Irish Workhouses Suffering and Survival

When I was planning my trip to Ireland, it was very important to me to visit Irish Workhouses. My grandmother's family immigrated from Ireland in the 1850s, after surviving the Great Hunger, and the workhouses. I wanted to better understand my heritage, and the depths of horror they endured, so I routed our itinerary to the .

Visiting Portumna was educational, enlightening, and emotional. When I returned home, I was anxious to tell friends of this experience, and how it impacted me. I was proud to learn of the strength and the tenacity of the Irish spirit that my ancestors must have had, and that I identified with. I was sadly surprised to find that no one even knew what the Irish Workhouses were.

Over 33 million Americans claim to have an Irish heritage or ancestry, but very few know of the Irish Workhouses. They can cite many facts and myths about Ireland, with St. Patrick and the Catholic Church topping the list, closely followed by potatoes, the famine, and the long-standing conflict with Great Britain. Yet, each of these pieces of history is interwoven with the history of the workhouses.

The History Of Irish Workhouses

Huge waves of desperate poor emigrated out of Ireland in the mid to late 1800s, to escape and avoid, the workhouses, starvation, and the oppression enforced upon them by the British. Their posterity and heritage spread throughout the western world. The descendants of the Irish around the world outnumber the citizens of Ireland, by 7 times!

Of course, the Irish themselves have tried to push the workhouses from their memories. They were not the inherent reason for their suffering, rather a symptom of the overall degradation. But their presence of a workhouse in nearly every community, and their detestable conditions resulted in them becoming a symbol of the suffering, and all of the wrongs put upon the Irish people for centuries.

This all started all the way back in the 12th century. Prior to that, Ireland was an independent country, with a traditions, and language. There were small kingdoms across the land, and the rulers of each reporting to a singular, High King. The Norse, commonly referred to as Vikings, had established footholds throughout north-western Europe, but it was in the 1170s when a powerful Anglo-Norman invasion took place, and the last High King of Ireland, Roderic O'Connor, was defeated, that gave Henry II the opportunity to take control of Ireland.

For 6 centuries, Ireland was ruled by England, through a system of Earldoms, with each Earl reporting to the throne of England, with all of the laws and taxes that typically came with that rulership. A series of attempted overthrows took place, but the English authority remained intact through each. It was in the early 18th century when a most detrimental blow to the Irish people took place: the enactment of the Penal Laws.

The Oppression of The Irish People

At that time, nearly 75% of the population of Ireland were poor Catholics. The Penal Laws punished them for their faith. Catholics were forbidden from practicing their religion, from teaching, entering the army, any civil service position, or legal profession. They could not own a horse worth more than 5 pounds, own or bear arms. They could not purchase land. If a Catholic already owned land, it would be divided among his successors upon his death, but, if one heir converted to the Protestant religion, he became the sole owner, leaving his siblings with nothing.

Within 100 years, the majority of the Irish became homeless laborers, with no available work. The majority survived by what was known as the Conacre system. A landowner (a Protestant English citizen) rented small cabins and a plot of land large enough to graze a cow and raise a garden of potatoes, to a laborer for a single season. The worker was "paid" for his work, and his rent was taken from his earnings. The poor had little money for anything but rent, but they at least had food. If the laborer did not "earn" enough to cover his rent, he would be evicted.

Read about the Conacre system to get a better understanding of the dire situation these Irish families were placed in.

By 1800, when the British monarchy fully claimed ownership of Ireland, it then had to assume responsibility for the conditions. One Royal Commission after another assessed the problem of poverty in Ireland and enacted laws to “improve” the situation, which had virtually no effect. They enacted the Public Works Act, through which Irish poor were hired to build roads, and other such infrastructure needs. However, the poverty was too extensive, and too little work was available. In 1838 it was finally determined that the power of the Poor Law Commissioners, who oversaw workhouses in England and Wales, would be expanded to Ireland.

Ireland was divided into 130 "Unions", which were based upon the already existing Townlands system.Each Union had an elected board of governors, but only ratepayers (tax paying landowners) could vote. In January 1839, architect George Wilkinson was hired to design and oversee the construction of a workhouse for each union. The overall design was the same for each newly built construction, with cost and durability being the primary concerns.

The Conditions Of An Irish Workhouse

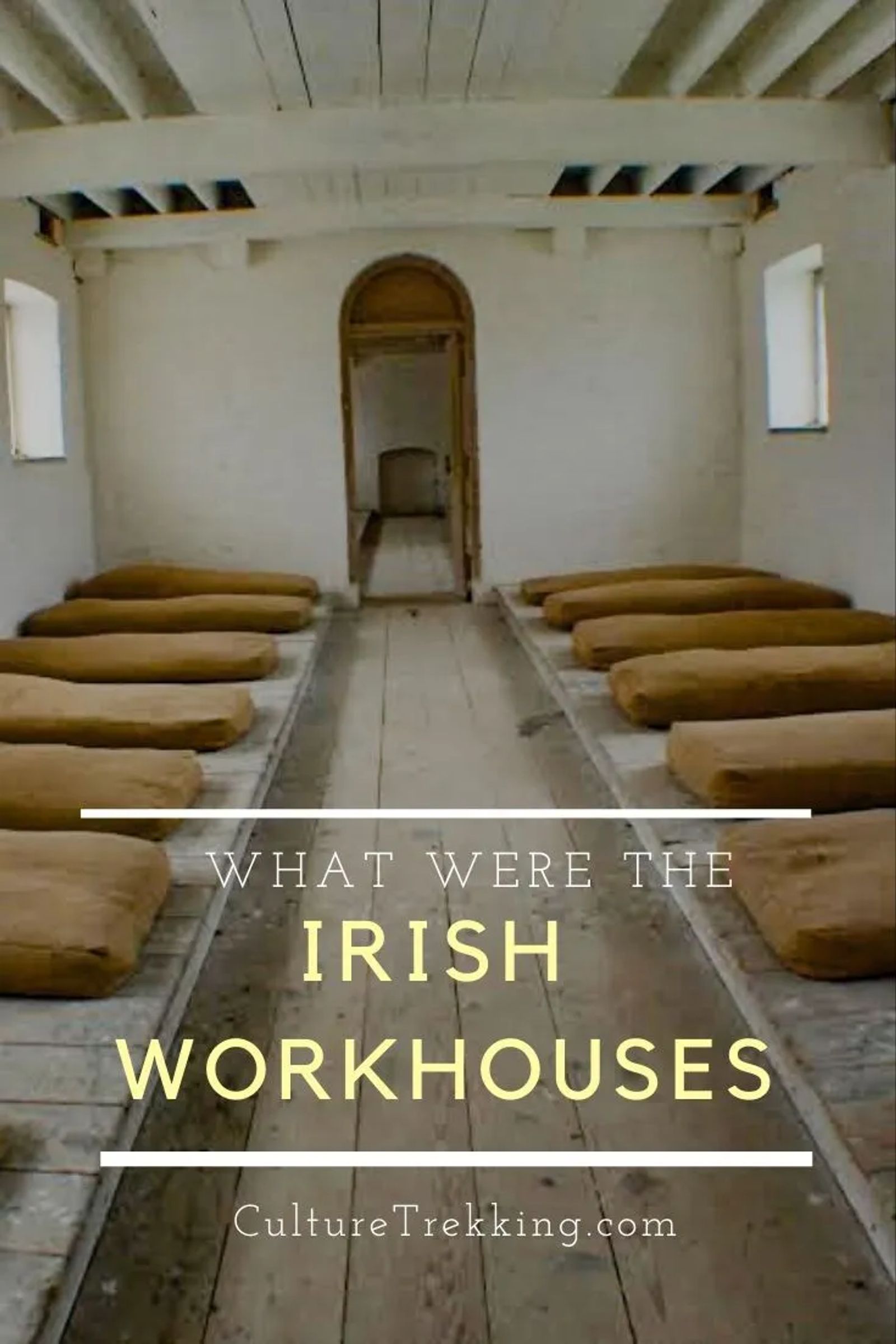

The typical setup of the workhouse, became known as an H Block style, with the structures set up in the formation of a letter H. There was a central acceptance building, which also housed the governors meeting rooms, and the storerooms, and on each side were the male and female dormitories.

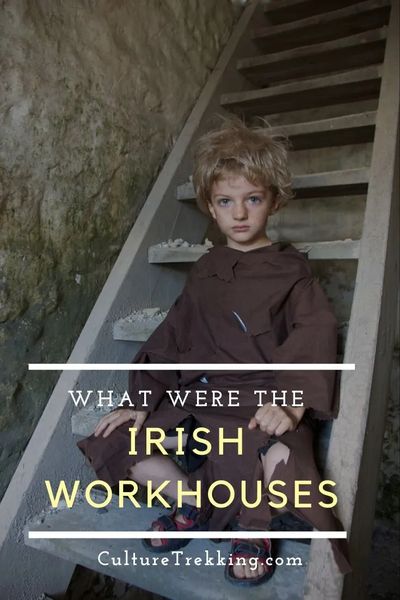

Life at the workhouse was meant to be unpleasant. It was a common belief that poverty was a result of laziness. Workhouse life was to be so undesirable that it would only be seen by the poor as the last resort. Workhouses in England and Wales already had dozens of rules and restrictions, but those in Ireland were even harsher. Read the rules of the workhouses.

Any citizen who owned even the smallest parcel of land could not enter the workhouse without turning over the ownership of this land. Any citizen so destitute they sought sustenance at the workhouse could not enter the workhouse unless his entire family also came to the workhouse.

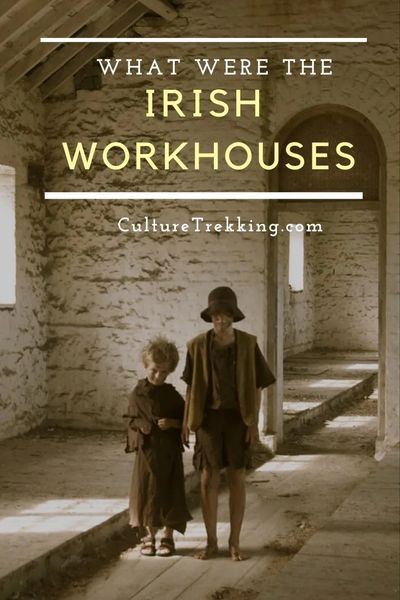

Upon entry, the destitute and starving citizens would often be required to prove their need, sometimes although many were near death. They would be inspected, medically assessed, and then split up. Families were required to enter together but they were not allowed to stay together. Only children under age 2 could stay with their mothers. Children from 3 to 15 were separated into the girls and boys dormitories. At 16 they were treated as adults and separated into the men's and women's dorms.

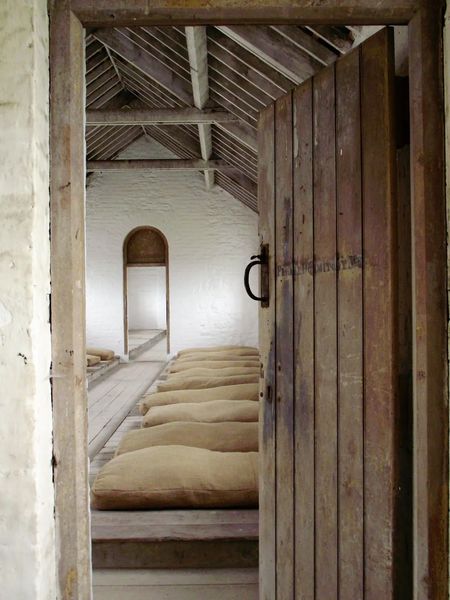

The dormitories were set up in stark white fashion, with the walls lime washed, for sterilization purposes. Bedding consisted of straw mats laid in rows on the floor. Heating was provided by a single fireplace at one end of the room, so those at the far end received little warmth at all.

Anyone unable to support themselves outside of the workhouse would be required to work, for their keep, while in the workhouse. Sitting idle, at any time, was not allowed. The women attended to the housekeeping tasks, including cooking, cleaning, laundering, and mending. Laundry included boiling linens in huge vats and laying them out overheated metal piping.

Mens work included breaking stones, cutting wood, and tending the land around the workhouse, as well as physical repairs on the structures themselves. Even the elderly and infirm had duties to their abilities, which included picking oakum. This was a process where lengths of used rope, such as from fishing boats, were unwound strand by strand, to pick out the impurities. This same task was often given to prisoners as punishment. The rope could be rewound and sold by the workhouse for profit.

Sunday was a day of rest. During the winter months inmates were allowed to rise an hour later and did not start work until 8:00 am.The general work schedule of the inmates including a 10-hour workday, starting at 0700, with a one hour break for the lunch/dinner meal. Despite this labor, it was expected that the diet in the workhouse would be less satisfactory than the typical diet of those outside of the workhouse in the community. Since most Irish were in a dreadful state of poverty, they were eating very little. So the diet in the workhouse consisted of 2 meals per day for adults, a breakfast of a thin oatmeal porridge, called stirabout, and a bunch of potatoes and milk. Children were more fortunate, being afforded a supper, which consisted of bread and milk.

Conditions in the workhouse were miserable as planned, but the staff hired by the elected board of governors often let them go beyond deplorable. When inspections did occur, there were often notes in regards to the sad state of hygiene and health of the inmates.

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

The Potato Blight and the Great HUnger of Ireland

In 1945 a potato blight spread throughout western Europe, causing the potato crop to go black, and die. Although this impacted millions of people, nowhere was it as devastating as in Ireland, where the poor lived on potatoes for sustenance. Had this blight affected only one year, recovery may have been possible, but it continued for 4 years. Over a million Irish died of starvation during the famine, and it became known as the Great Hunger.

The saddest fact of the famine was that other crops were growing in Ireland, as well as livestock. But wealthy landowners and farmers continued to sell and export this food, while the poor Irish starved.

The workhouses were designed to house 600 to 800 persons each, but more and more citizens who could no longer bear the hunger sought a refuge. At times as many as 1200 poor would be present in these workhouses on a given day. The school rooms and even stables were used to house inmates. Waves of disease spread through, and large numbers of inmates died. In some cases, mass graves were used.

The Mass Emigration

Conditions were so bad, that in 1848 the British government finally took two further actions. They began actively supporting emigration. The landlords greatly supported this, because the fewer people there were on their land, the lower their rates, or taxes, were.

Hundreds of thousands of the poor saw emigration as their most viable option and left by whatever means they could, many with a term of indenture. Conditions on the transport ships were horrid, and thousands died of disease during the voyages, to be buried at sea.

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

The Laws of the Workhouses

The government also voted to expand the Poor Law Unions, adding another 32 unions. The Workhouse which I visited, in Portumna, was one of the additional 32 established. Built in 1852, it came into existence after the worst of the Great Hunger. Nonetheless, the available records make the despair of conditions clear.

From the beginning, the ratepayers opposed the establishment of this Union, voting to abolish it and send the paupers elsewhere. They were overruled by the Dublin Commission. It is also clear, that despite the poverty and suffering of the people, that many saw the workhouse as economic opportunities.

Even priests and chaplains argued over salaries and refused to provide their services, even to minister the dead. Farmers signed contracts to provide food of certain types and qualities, but instead failed to meet the terms of their contracts, or provided food of a far inferior quality.

Portumna was a smaller workhouse built to house 200. Most of the time it was open, it's occupancy was around 125. Still, it's history is one filled with sorrow, suffering, and loss. Today, it is one of few left standing in almost it's complete original composition.

The End of the Irish Workhouses

During the Irish Revolution, in the 1920s, many of the workhouses were burned down by one side or the other, to prevent the opposition from using the houses as a military base. Once Irish freedom was won, the remaining workhouses were shut down, but the buildings were used for county hospitals.

Over the decades after the closure of the workhouse, and then the closing of the hospital, the Portumna structures were used for many things, housing different businesses, including a knitting company, an agricultural show, a textiles company, and a packing company, then warehouses and storage, then sat vacantly. It wasn't until the 1990s that today's center was envisioned. The following is from the Workhouse Centers informational materials:

Portumna Workhouse is one of the last remaining buildings of its kind in Ireland and a conservation order was placed on it which ensures its structural survival. The complex lay derelict and covered with ivy for a number of decades and in 1999 South East Galway Integrated Rural Development Company, a voluntary local development group, approached the Western Health Board with a view to conserve the site and reusing it for the benefit of the area.….. The Irish Workhouse Centre opened to the public in 2011 and tells the story of the Irish workhouse as an institution. The project is led by a voluntary board and a team of local volunteers guide the visitors around the complex.

The story of Portumna is unique. It has been said that the workhouse is regarded as the most despised of all institutions ever imposed upon Ireland, representing all of her people's suffering. But it is a history that must be told and remembered, and the Portumna Workhouse Center has taken on that task. Gradually they have worked to restore the center, as time and funds are available.

As said at the onset of this story, I visited Portumna to connect with my own family history. My grandmother's family experienced the misery of the workhouse, before escaping to the United States. Walking through the dormitories, seeing the straw mats, seeing the laundry vats, hearing the stories, understanding the separation of husband and wife, mother and child, was powerful in itself. To know that my family survived this life, was overwhelming.

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

Are the Irish Workhouses Worth Visiting?

I cannot hope to truly convey the suffering and the fear of the poor Irish, nor their hatred for the workhouses and the landowners. Seeing it first hand gives a glimpse. If you have Irish ancestry, you owe it to yourself to understand this heritage, and the strength it took to bequeath you with the life you have today. Visit the Portumna Workhouse Center if the chance arises.

To be honest, the experience was so absorbing, that I never had the thought of taking my camera from my bag. It is only thanks to the volunteer staff at the Portumna Workhouse Center that I have photos to share.

Where To Stay Near Portumna

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600)

About the Author: Roxanna Keyes is a mom, grandma, and a Senior Distribution Manager, for the US Postal Service, in central Illinois. While she has dedicated a significant portion of her life to her career, she has learned that life, and making a living, are not the same thing, and too many of us confuse the two. She started her blog Gypsy With a Day Job to encourage others to recognize that fact before it is too late and to inspire them to see the world, and to live out the adventures that make the stories of their life worth sharing.

Welcome to Culture Trekking!

My name is Janiel, I specialize in solo female travel, cultural connections, sustainable adventures, food and history to help make your travel experiences fun, meaningful, and delicious. My experience in travel, and my personal story have allowed me to get published in Fodor's Travel, Atlas Obscura, Metro.co.uk, Trip Advisor, and multiple Podcast interviews. You can find me on pretty much every social media channel YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, TikTok. To read more about me and my story click here. If you are a brand and would like to work with me, click here.